Spectacles of Rome: Bathing, Blood, and Chariots (Part 1 Bathing)

You’ve had an exhausting day

- At work

- Watching the kids or grandkids

- Completing a project that has been bugging you for too long

You need a break—maybe a small celebration. So you call a friend to go out for a bath.

If you were an ancient Roman, that is exactly what you would do, except the ancients did not save this experience for special occasions. Group bathing in the large public thermae or a smaller private balnea was part of daily life. If you were wealthy or middle class, visiting the baths might be as routine as taking a daily shower. Thanks to government subsidies, even the poor could afford to bathe a few times a week.

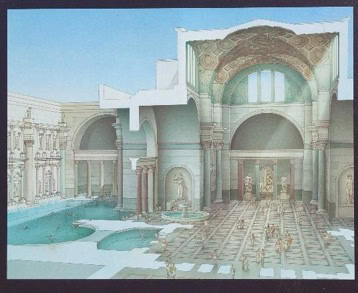

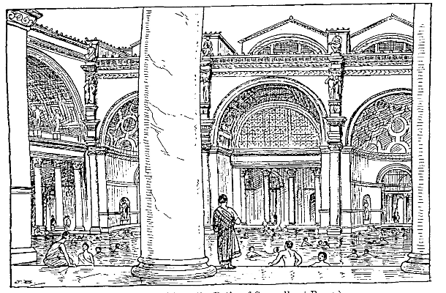

Roman bathhouses were more than places to clean up. These sprawling complexes were more like modern-day spas. Picture massage tables, exercise and game rooms, eating establishments, hairdressers, and manicurists. The grander baths, often commissioned by the emperors to showcase their generosity and win public favor, featured outdoor swimming pools, gymnasiums, parks for leisurely strolls, theaters, and libraries. Despite these luxurious extras, the main attraction was always the bath itself. It was a social event, a chance to catch up with friends, meet new people, or even conduct business, although the atmosphere could get boisterous and loud.

People bathed in the nude, so each bathhouse included a dressing area and at least three essential rooms with pools or tubs of varying temperatures.

- Tepidarium – warm and inviting

- Caldarium – intensely hot

- Frigidarium – cool-cold, like stepping into a refrigerator

Re-created bath scene inside the remains of a public bathhouse in Bath, England See the inset for a picture of the hypocaust columns supporting the floor above the furnace in the caldarium. (Bath, England)

Slaves kept the bathhouses running, tending furnaces beneath tiled floors to heat the rooms and water. In some complexes, an additional sauna-like hot room was available. Bathers moved between rooms in whatever order they preferred. In Fortunes of Death, my second book, there’s a scene where Sabina, follows a typical Roman bathing routine—starting in the tepidarium, soaking in the caldarium, and finishing with a bracing dip in the frigidarium or an outdoor pool. In book three Powers of Death a deserted bathhouse is the perfect setting for murder.

“The Roman ingenuity in engineering and architecture is truly remarkable. Their ability to create functional, luxurious, and climate-adaptive spaces like the baths speaks volumes about their understanding of materials, design, and human comfort.” (Chatgpt)

“The Roman ingenuity in engineering and architecture is truly remarkable. Their ability to create functional, luxurious, and climate-adaptive spaces like the baths speaks volumes about their understanding of materials, design, and human comfort.” (Chatgpt)

Hygiene was a central part of the Roman bath experience. Oil would be spread over the body then the day’s sweat and grime were scraped away with a curved brass tool called a strigil. Wealthier patrons had servants perform this task, while others managed it themselves.

then the day’s sweat and grime were scraped away with a curved brass tool called a strigil. Wealthier patrons had servants perform this task, while others managed it themselves.

Roman propriety typically kept the genders separate. Women usually bathed during reserved hours in the morning, and men in the afternoon. Although bathing was generally viewed as healthy and beneficial, some considered it indulgent and disreputable, associating it with too much wine, luxurious food, and sex, especially in cases where mixed-gender bathing occurred.

Roman propriety typically kept the genders separate. Women usually bathed during reserved hours in the morning, and men in the afternoon. Although bathing was generally viewed as healthy and beneficial, some considered it indulgent and disreputable, associating it with too much wine, luxurious food, and sex, especially in cases where mixed-gender bathing occurred.

Baths of Caracalla: Valina Tsikalá, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Badenweiler, Germany bathhouse model Brücke-Osteuropa, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

https://Commons.Wikimedia.org/Wiki/File:Dialogues of Roman Life.djvu

Grounds User:Ethan Doyle White, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Strigil Toyotsu, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Baths of Caracalla Painting by Virgilio Mattoni, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons