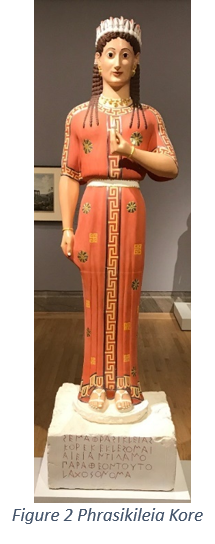

Although the first Phrasikileia Kore statue is the original funeral statue of a young maiden, excavated from a Greek archeological site in 1972, the second, a reproduction, is how the statue initially looked when it was created around 540 B.C.

I.Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

R.Marthaler, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

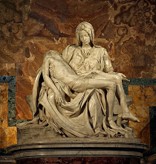

We are accustomed to seeing sculptures from antiquity presented as bare white marble. After centuries of weathering, oxidation, sun, and dirt, most colors have been erased or become invisible to the naked eye. We are not alone. When traces of pigments were found on ancient artifacts, most archeologists dismissed them as sullying the pristine white art form and, sometimes, intentionally scraped the coloring off. Artists of the Renaissance, like Michelangelo and Raphael, based their works on what they believed to be the norm of Greek and Roman art and highlighted the natural monotone of the stone. (see below Michelangelo’s Pieta.)

Michelangelo, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/> via Wikimedia Commons

The idea that Greeks and Romans wanted their statuary to look humanly realistic is a recent paradigm shift. Over the last three centuries, the growing evidence for statues in living color was rejected or ignored by many in the world of antiquities. Look closely at the first original statue.

Can you see the faded coloring and pattern of her dress? Phrasikileia Kore’s statue was found carefully buried in the ancient Greek city of Myrrhinous (modern Merenta). The exceptional preservation of the statue and the intact nature of the polychromy or colored elements makes the Phrasikleia Kore one of the most important works of Archaic art exhibited at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. (1)

Although much of the original coloring is not visible to the naked eye, archaeologists use UV light to discover that ancient sculptures were “all” completed with a final coat of vibrant paint. Statues clothed in togas and tunics in dazzling colorful patterns, natural hair, eye coloring, and differentiated skin tones were placed in temples decorated with equally colorful frescos and wall paintings.

The Archer from the western pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on Aigina; reconstruction, color variant A from the Gods of Color exhibit.

R.Marthaler, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0> via Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Marsyas, CC BY-SA 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5> via Wikimedia Commons Ronald Slabke/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0

The German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann has spent the past twenty-five years recreating the kaleidoscope glory that was Greece. His full-scale reconstructions use ultraviolet light, cameras, plaster casts, and powdered minerals in the same organic pigments used by the ancients: green from malachite, blue from azurite, yellow and ocher from arsenic compounds, red from cinnabar, black from burned bone and vine. His statues have toured the world, making their debut in 2003 at the Glyptothek Museum in Munich, and the Museum at Harvard University in an exhibition called “Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture of Classical Antiquity.” Selected replicas were also featured in “The Color of Life” at the Getty Villa in Malibu, California.

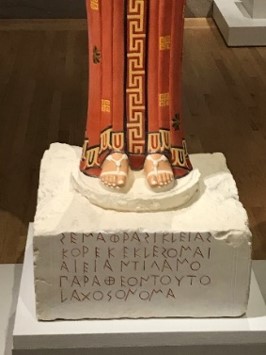

PostScript. Phrasikileia Kore

R.Marthaler, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0> via Wikimedia Commons

Although many statues represent mythological gods, the funerary statues are in remembrance of real people. Phrasikleia is an ancient Greek word meaning ‘fame.’ The word would have had significant meaning to her family, the Alcmaeonid’s. The statue honors a young woman by using the symbolism of her jewelry and the lotus flower she is holding. The lotus repeated on the crown she wears is thought to mean “plucked before it could bloom,” representing her status as a virgin and unmarried woman at the time of her death. (2) (1) The inscription agrees.

Tomb of Phrasikleia.

Kore (maiden) I must be called evermore; instead of marriage, by the Gods this name became my fate

(1) Stieber, Mary C. The Poetics of Appearance in the Attic Korai. 1st ed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004. p. 1.

(2) Gods in Color, "Reconstruction of the Grave Statue of Phrasikleia, 2010." San Francisco: The Legion of Honor.

True Colors | Arts & Culture| Smithsonian Magazine

https://www.interestingfacts.com/fact/634613bd6da7e90008a47850

Essayist and cultural critic based in New York City, author Matthew Gurewitsch.

Why We Need to Start Seeing the Classical World in Color (hyperallergic.com)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_sculpture