To us, classical Greece means white marble. Not so for the Greeks, who thought of their gods in living color and portrayed them that way too.

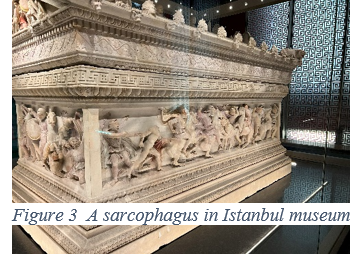

Alexander’s Sarcophagus (named not for the king buried in it but for his illustrious friend Alexander the Great, is depicted in its sculpted frieze showing his successful battles of conquest. The earlier statues and friezes were painted in a flat paint-by-number simplicity. However, as the centuries progressed, so did the artists’ skill, and subtle shading and muted contrasts began appearing in the temple and funerary artwork. But paint wasn’t the only way the Greeks decorated their statues and artwork.

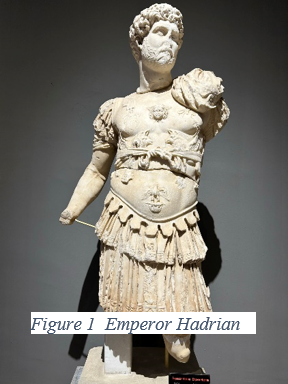

When a new Parthenon was erected in Athens between 447 and 438 BCE, the new building was not intended to be a temple but a treasury meant to house the colossal Chryselephantine statue of Athena Parthenos. The statue was considered the ultimate financial reserve. The gold decorating it could be melted down if necessary. According to ancient authors, the weight of gold used was between 1 and 1.3 tons of gold. The quantity and cost of the ivory used for the statue’s face, arms, and feet, as well as for the gorgon’s head depicted on the goddess’s chest, is more difficult to estimate. Finally, the ivory was painted: the goddess was “made-up,” using red pigment on her cheeks, lips, and nails. It is also very unlikely that the gold was left as is: it would likely have been inlaid with precious and semi-precious stones that reflected the light.