[[File:Alfredo Tominz – The chariot race in the Circus Maximus.jpg|Alfredo_Tominz_-_The_chariot_race_in_the_Circus_Maximus]]

Have you ever wanted a rival sports team to lose? How about wishing revenge on a failed love relationship or their new love? Not happy with the opposing political view? Did someone ever steal from you or cause you harm? The natural way of man is to wish for a bit of payback. The Romans did more than wish, they took action, and their curses addressed everything: politics, employee-employer agreements, broken promises, and of course, love and sex. You could curse your rivals in sport and business to fail. Opposing sides in legal disputes were cursed with loss of memory and speech impediments. Here are a few curses that would ensure a satisfactory ending.

Translation: “I implore you, spirit, whoever you are, and I command you to torment and kill the horses of the green and white teams from this hour on, from this day on, and to kill Clarus, Felix, Primulus, and Romanus, the charioteers.” (6)

The most frequently cursed animals on these tablets were horses, given their importance in chariot races. The side opposite the curse included a crude depiction of an anatomically correct deity, presumably to aid in ensuring the rival teams failed. (6) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Puy-du-Fou-4.JPG

Translation: “Docimedis has lost two gloves and asks that the thief responsible should lose their minds and eyes in the goddess’ temple.” (6)

Bathhouse thefts were widespread, and Docimedis lost his valued gloves while soaking in a pool. He must have placed a high value on them to ask for this kind of eternal punishment. (6)

Translation: “The human who stole Verio’s cloak or his things, who deprived him of his property, may he be bereft of his mind and memory, be it a woman or those who deprived Verio of his property, may the worms, cancer, and maggots penetrate his hands, head, feet, as well as his limbs and marrows.” (6)

Here are two nasty curses, one directed at Porcello and another the Senator Fistus.

Translation: “Destroy, crush, kill, strangle Porcello and wife Maurilla. Their soul, heart, buttocks, liver …”

Translation: “Crush, kill Fistus, the senator. May Fistus dilute, languish, sink and may all his limbs dissolve …” (7)

People took these curses seriously and to make the curse extra effective, they would break into tombs and grave sites to place their curse next to a murdered victim’s corpse or ashes.

The Christian faith exhorts believers to offer forgiveness, and these revenge curses would have been condemned, but curses attributed to pagans, Jews, and Christians have been found written on graves. Grave robbing was not just an Egyptian phenomenon. Gifts buried with the deceased could include clothing, jewelry, or a favorite household item, even the urns that housed the deceased’s ashes were fair game for grave robbers. With the lack of a police force, fear of arrest was not a deterrent. So how about fear of the deceased’s ghost haunting you? Punishment in the afterlife? How about suffering a lingering and painful death? These curses were often painted in red ochre, a universal warning color, and were occasionally accompanied by diagrams for the illiterate grave robber.

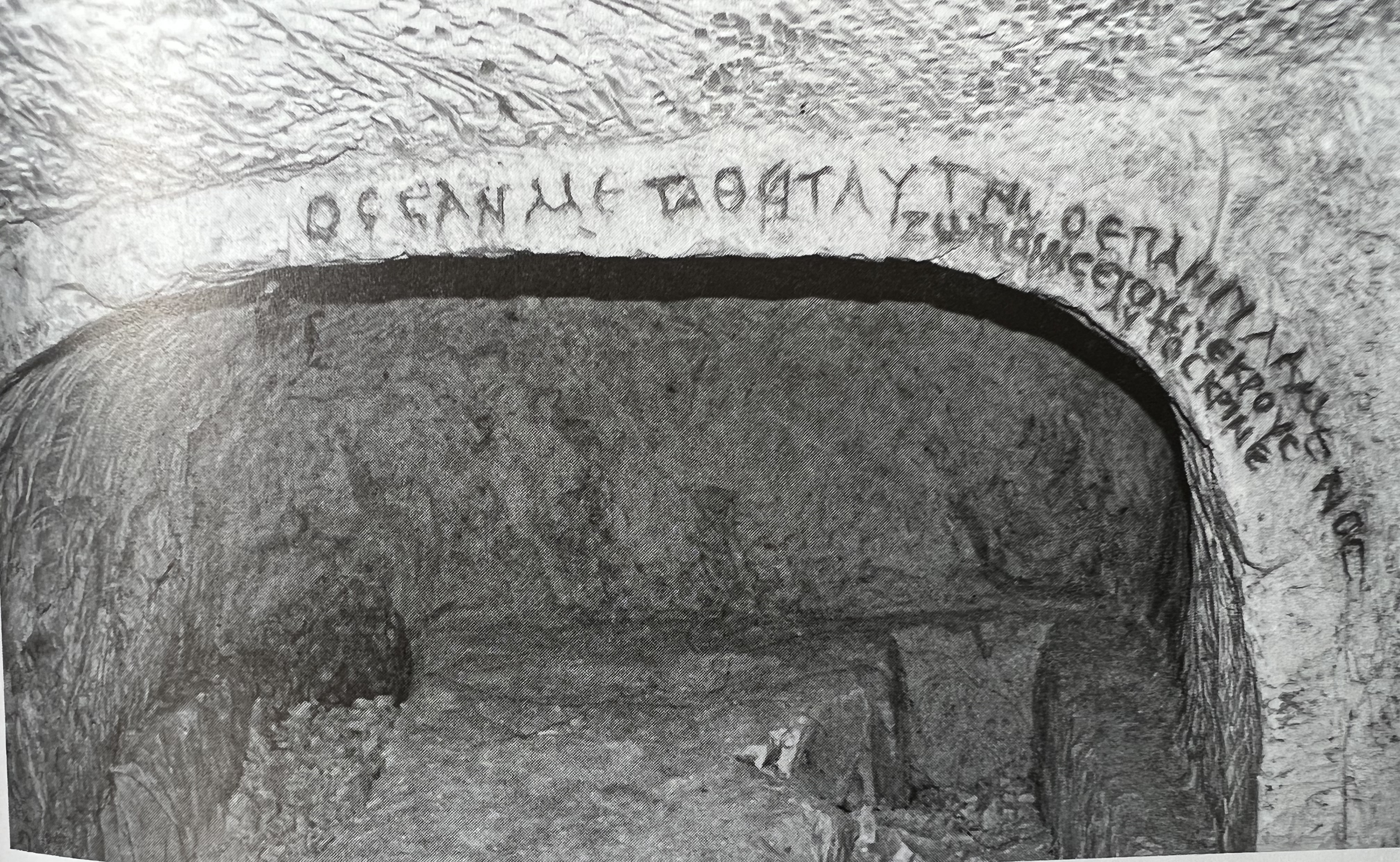

Stern, K. B. (2020). Writing on the wall:Graffiti and the forgotten jews of antiquity. Princeton University Press. photo by Ezra Gabbay

These curses were carved into the stone above tombs in the Roman catacombs and were intended to keep grave robbers from entering or disturbing the burial places of the deceased.

“Anyone who shall open this burial upon whoever is inside it shall die of an evil end.” (9)

“Anyone who changes this lady’s place, He who promised to resurrect the dead with Himself judge him.” (9)

Catacomb: an underground cemetery made up of tunnels and passageways with recesses for tombs. You can stroll among the graves in Rome, Paris, and other locations.

One curse, written in red paint on stone at an ancient grave in Beit She’arim, reads “Jacob the Proselyte vows to curse anybody who would open this grave, so nobody will open it.” As translated by Jonathan Price, professor of ancient history at Tel Aviv University. (10)

Pliny viewed magic as ineffective and disreputable, yet he states it contains “shadows of truth,” particularly in the “arts of making poisons.” And “there is no one who is not afraid of spells.” He did not recommend amulets and charms for protection but did not deride them either, acknowledging “that it was better to err on the side of caution, for, who knows, a new kind of magic, a magic that really works, may be developed at any time.” (1)

“The emperor Constantine I the 4th century AD/CE issued a ruling to cover all charges of magic. He distinguished between helpful charms, not punishable, and antagonistic spells.[12]

Saint Sebastian catacombs Appian Way

Saint Sebastian catacombs Appian Way

Roman authorities ruled what forms of magic were acceptable and which were not. Those that were not acceptable were labeled “magic.” At one point, crucifixion was the penalty for using curse tablets. But even death didn’t stop their sale and use. Acceptable mystical practices were typically traditions and practices within the state’s religions. (1) Decisions affecting the empire were often based on augury, the practice of interpreting the will of the gods by observing bird behavior. Haruspication, which involved inspecting the entrails of animals sacrificed to the gods, became a more respected and popular form of divination.

A bronze reproduction of the so-called “Liver of Piacenza”, an animal liver engraved with the Etruscan names of the deities connected to each part of the organ. Lokilech, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

A bronze reproduction of the so-called “Liver of Piacenza”, an animal liver engraved with the Etruscan names of the deities connected to each part of the organ. Lokilech, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

Christians often defended themselves against accusations that they possessed magical powers giving them control over supernatural forces. In the Passion of Perpetua and Felicitas narrative, the Roman Tribune (judge) feared the two Christian women would magically disappear from prison before their execution at the celebration of Emperor Septimius Severus’s birthday. (11)

A letter from the emperor Hadrian accused the Christians, Samaritans, and the chief of the Jewish synagogue of being astrologers, soothsayers, and anointers. Christians always rejected the charges and disputed being called magicians, answering that Christians abhor magical arts. (8)

Orthodox Christians exorcised demons, and references to exorcisms, healings, and prophesying are numerous. Those outside the church equated that power to magic. The church leader Irenaeus writing the second century AD/CE, stated, “Some do certainly and truly drive out devils,…yet the church does nothing by angelic invocations or by incantations, or by any other wicked curious art, but directing her prayers to the Lord…and calling upon the name of our Lord Jesus Christ.”

Saint Benedict Stories by Spinello Aretino (b. ca. 1345, Arezzo, d. 1410, Arezzo) Stories from the Legend of St Benedict 1387 Fresco S. Miniato al Monte, Florence The scene represents the Exorcism of St Benedict. — Keywords: ————– Author: SPINELLO ARETINO Title: Stories from the Legend of St Benedict Time-line: 1351-1400

Book of Luke 10:8-9,17

Whatever city you enter, and they receive you, eat such things as are set before you. And heal the sick there, and say to them, ‘The kingdom of God has come near to you.’…Then the seventy (disciples) returned with joy, saying, “Lord, even the demons are subject to us in Your name.”

Old magic or new evidence of evil, immorality, and wicked influencers abounds in the world. Justin Martyr, a venerated Saint of the early Christian church, knew the challenges well and the final victory. Before his martyrdom, he testified, “The concealed power of God was in Christ the crucified, before whom demons, and all the principalities and power of the earth, tremble.” (8)

- Magic of ancient Romans « IMPERIUM ROMANUM

- Brenk, E. (1977). In Mist Apparelled: Religious Themes in Plutarch’s “Moralia” and “Lives”. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 59. ISBN9789004052413.

- Tatum, J. (1979). Apuleius and the Golden Ass. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 28–29.

- Mystakidou, Kyriaki; Eleni Tsilika; Efi Parpa; Emmanuel Katsouda; Lambros Vlahos (1 December 2004). “Death and Grief in the Greek Culture”. OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying. 50 (1): 24. doi:10.2190/YYAU-R4MN-AKKM-T496. S2CID144183546. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- 11 of the Most Infamous Ancient Curses in History – Oldest.org

- 7 Ancient Roman Curses You Can Work into Modern Life | Mental Floss

- Ancient Roman Curses Translated – The Language Blog by K International (k-international.com)

- Benko, Stephen. Pagan Rome and the Early Christians. Indiana Univ. Press, 1986.

- Stern, K. B. (2020). Writing on the wall: Graffiti and the forgotten jews of antiquity. Princeton University Press.

- Disturbing Red Painted Curse Discovered In Jerusalem Catacomb | Ancient Origins (ancient-origins.net)

- The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity – Wikipedia

- Magic in the Greco-Roman world – Wikipedia

- Ancient Spells and Charms for the Hapless in Love | Ancient Origins (ancient-origins.net)