Imagine living in a society where a version of Halloween exists in everyday life. I don’t mean candy and costumes but the serious business of navigating malevolent demons, fickle goddesses, evil portents, and the neighbor down the street paying the local magician to curse you.

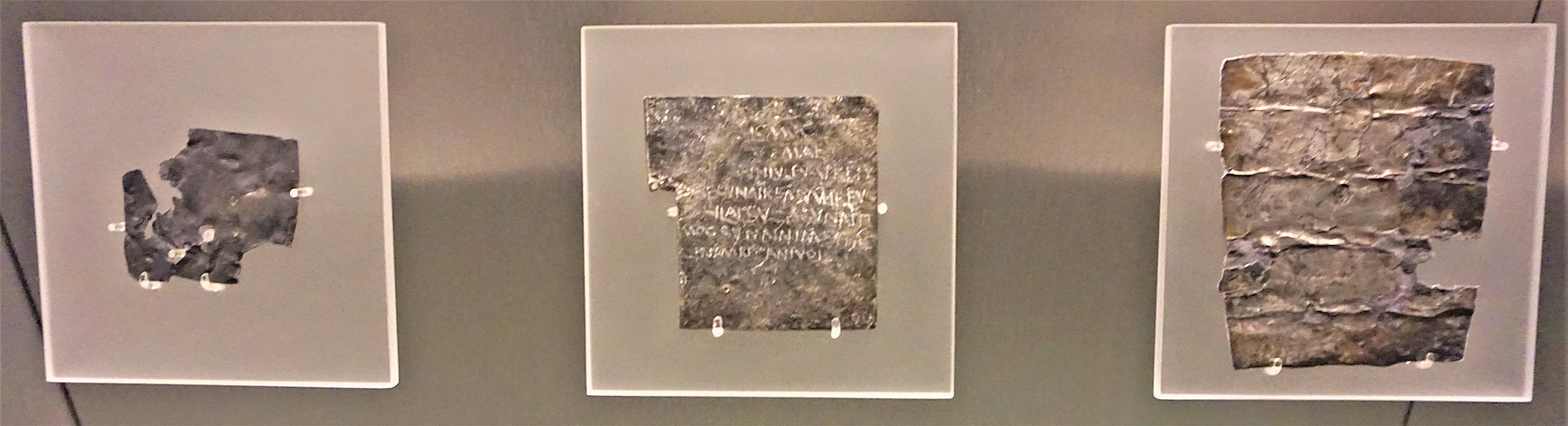

Archeologist have found thousands of curse tablets in countries that were part of the Roman Empire. One found in Greece, contains this curse written by someone jealously in love with a man called Kabeira who tries to damn his wife Zois: (13)

Archeologist have found thousands of curse tablets in countries that were part of the Roman Empire. One found in Greece, contains this curse written by someone jealously in love with a man called Kabeira who tries to damn his wife Zois: (13)

I assign Zois the Eretrian, wife of Kabeira, to Earth and to Hermes — her food, her drink, her sleep, her laughter, her intercourse, her playing of the kithara, and her entrance, her pleasure, her little buttocks, her thinking, her eyes…

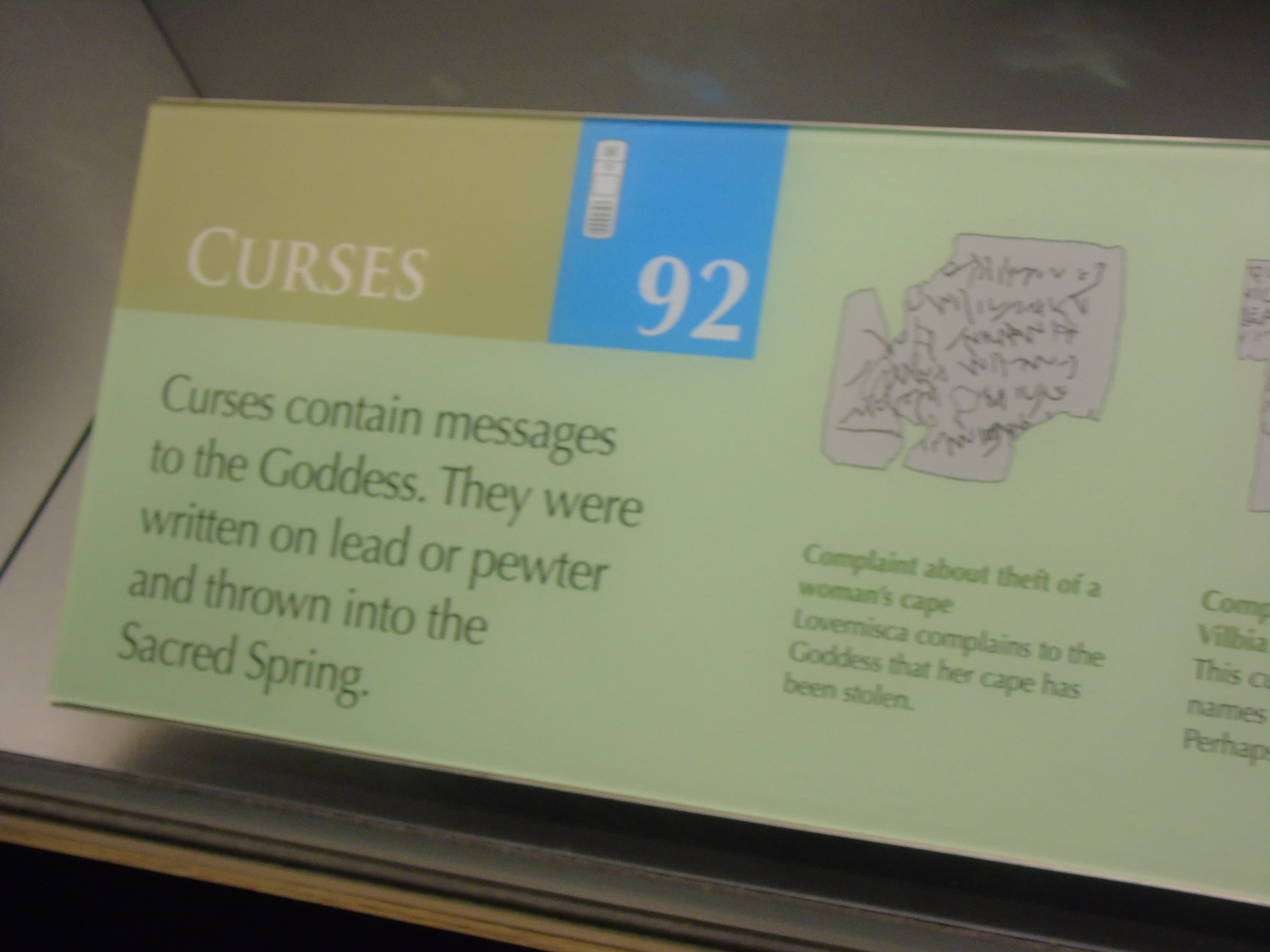

Curse tablets. Pic. By Joyofmuseums – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65535299

Fernando Losada Rodríguez The Roman Baths.025 – Bath.jpg

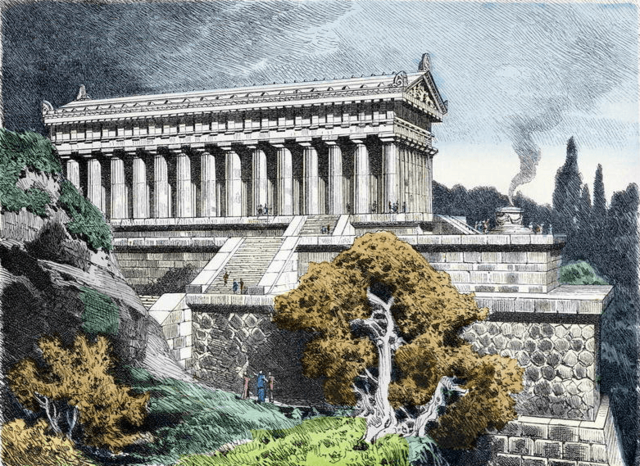

The city of Ephesus, located in modern-day Turkey, was a hot spot for the magical arts. Two thousand years ago, during the setting of my books, Obedient unto Death and Fortunes of Death, superstition and magic permeated nearly every aspect of life, from birth to death. The Ephesian Letters were six secret words believed to contain magical powers to ward off demons and evil spirits. The letters originated in Ephesus, and the magicians who possessed those frightening six words commanded high fees to engrave them on amulets or recite them in spells.  Temple_of_Diana_at_Ephesus_by_Fedinand_Knab_(1886).png

Temple_of_Diana_at_Ephesus_by_Fedinand_Knab_(1886).png

The Apostle Luke records the Ephesian converts to Christianity renouncing magic and burning their books of magical papyri, spells, incantations, chants, and prayers. Books and scrolls were expensive, so this was a financial and religious statement about who the new followers of Christ believed controlled the unseen powers of the universe.

Archeological artifacts, literature, and ancient laws address superstitions and ancient magic throughout the Greek and Roman Empires from early BC to the late 5th century AD/CE. Abundant evidence exists of curse tablets, buildings, and mosaics decorated with magical themes and protecting spells, jewelry and amulets engraved with mysterious unintelligible symbols, and recipes using special herbs believed to ward off evil. Politicians, philosophers, and even emperors practiced and believed in these mystical arts to various degrees. Pliny the Elder, a well-respected naturalist, and writer in the first century AD/CE, wrote that magic had thoroughly embedded itself in medicine, religion, and the astrological sciences. (1)

l“The senses of men being thus enthralled by three-fold bond, the art of magic has attained and influence so mighty, that at the present day even, it holds sway throughout a great part of the world, and rules the kings of kings in the East.”

Lucio Massari – http://www.otherfood-devos.com/2012/01/is-it-time-for-burning.htm

Plutarch, a Platonist philosopher, who died in 119 AD/CE, accepted that daemons existed and served as agents or links between the gods and human beings and were responsible for many supernatural events in human life commonly attributed to divine intervention.2 Some daemons are good, some are evil, but even the good ones can do harmful acts in moments of anger. 2

A later Platonist, Apuleius, took the existence of daemons for granted. “They populate the air and seem to, in fact, be formed of air. They experience emotions just like human beings, and despite this, their minds are rational.” [3]

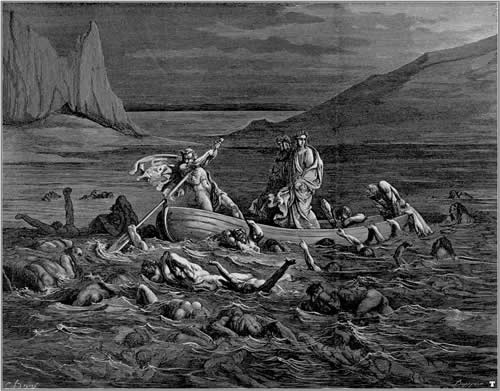

Like all cultures, the people of Rome and Ephesus wanted answers to the human question of what happens after death. Greeks and Romans accepted the existence of the soul after death. They believed the dead entered Hades or the underworld by crossing the river Styx in a boat. The ancients regarded Hades as a permanent state of murky darkness devoid of joy or conscious will. The afterlife was viewed by most as meaningless.[4] Where the dead flitted around without substance or purpose.

The philosopher, Plato, advocated the myth that the sons of Zeus judged souls branded with the scars of perjuries and crimes. The godless suffered eternal punishment in a level of Hades called Tartarus, and the righteous dead were sent to the Isles of the Blessed. However, the gods restricted the Isles of the Blessed to heroes who achieved great deeds. Crossing the Styx, illustration by Gustave Doré, 1861. Source: de:Bild:Styx-Doré.jpg (de:Benutzer:Dr. Meierhofer).

The philosopher, Plato, advocated the myth that the sons of Zeus judged souls branded with the scars of perjuries and crimes. The godless suffered eternal punishment in a level of Hades called Tartarus, and the righteous dead were sent to the Isles of the Blessed. However, the gods restricted the Isles of the Blessed to heroes who achieved great deeds. Crossing the Styx, illustration by Gustave Doré, 1861. Source: de:Bild:Styx-Doré.jpg (de:Benutzer:Dr. Meierhofer).

Perhaps Christianity rose in popularity because it offered an alternative belief that death wasn’t the end of a person’s existence. Christians believed Christ had conquered death after being crucified, buried, rising from the dead, and now lives eternally in the heavenly realm. Christians believed that they inherited Jesus’s resurrection, and that death had no dominion over them. Two thousand years later, they still profess, “I die with Christ and rise with Christ.”

There are conflicting accounts about whether pagans believed the dead could contact the living and visa-versa. Food was left at gravesites once a year, hinting at the dead returning to see if their relatives were honoring the deceased’s memory. What was agreed upon was the serious problem if you didn’t cross the river Styx, you would remain a wandering spirit or ghost – and not a happy one.

People believed malevolent spirits, including murder victims and those who died young, had more power to intervene with the gods to cause damage and harm. Their ghosts were invoked to carry curses inscribed on curse tablets to the underworld. The tablet asked for help from a particular deity to get revenge on someone by having that deity bestow catastrophe or misfortune upon them. In return, the person writing the message would promise to make offerings at their temple. (5)

A curse tablet would be deposited in a murdered victim’s grave or buried near the intended recipient of the curse. Anyone could hire a professional magician or sorcerer who would inscribe a curse on wood, pottery, or metal, especially if the curse issuer was illiterate. Lead was a favorite, but if you truly wanted to impress the gods, inscribing your curse on a gold or silver foil was sure to get their attention.

Have you ever wanted a rival sports team to lose? How about wishing revenge on a failed love relationship or their new love? Not happy with the opposing political view? Did someone ever steal from you or cause you harm? The natural way of man is to wish for a bit of payback. The Romans did more than wish. Read their curses and the charges of magic against the early Christians in Curses, Christians, and Catacombs Part 2

Viator.com Roman Catacombs Tours

- Magic of ancient Romans « IMPERIUM ROMANUM

- Brenk, E. (1977). In Mist Apparelled: Religious Themes in Plutarch’s “Moralia” and “Lives”. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 59. ISBN9789004052413.

- Tatum, J. (1979). Apuleius and the Golden Ass. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 28–29.

- Mystakidou, Kyriaki; Eleni Tsilika; Efi Parpa; Emmanuel Katsouda; Lambros Vlahos (1 December 2004). “Death and Grief in the Greek Culture”. OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying. 50 (1): 24. doi:10.2190/YYAU-R4MN-AKKM-T496. S2CID144183546. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- 11 of the Most Infamous Ancient Curses in History – Oldest.org

- 7 Ancient Roman Curses You Can Work into Modern Life | Mental Floss

- Ancient Roman Curses Translated – The Language Blog by K International (k-international.com)

- Benko, Stephen. Pagan Rome and the Early Christians. Indiana Univ. Press, 1986.

- Stern, K. B. (2020). Writing on the wall: Graffiti and the forgotten jews of antiquity. Princeton University Press.

- Disturbing Red Painted Curse Discovered In Jerusalem Catacomb | Ancient Origins (ancient-origins.net)

- The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity – Wikipedia

- Magic in the Greco-Roman world – Wikipedia

- Ancient Spells and Charms for the Hapless in Love | Ancient Origins (ancient-origins.net)