An author's dilemma – Slavery in ancient Rome

To the Romans, slavery was not a moral issue. They considered the subjugation of people to be:

· Economic; slaves were valuable property.

· Civil; the Romans needed slaves to build and maintain the empire.

· Reasonable: slavery provided an alternative to the punishment of death.

I found no records of general concern to humanize the laws governing slavery. For the most part, the ruling class agreed slaves had no personal rights apart from those granted by their masters. This view is not surprising. Rights were minimal to non-existent for most women, children, and non-Roman citizens who weren't slaves.

Most slaves were disposable labor and utilized in the dangerous jobs of mining, farming, quarry work, construction, metal smelting, and prostitution. In these jobs, slaves were treated as sub-human property. A person was stripped of any former identity and given a new name. Punishments were dispensed for offenses, real or imagined by the owner, and included flogging, branding, mutilation, disfigurement, and sexual assault. Ancient records document sporadic debate of the owner's right to kill or maim a slave for no reason.

A brothel in Pompeii

A book about farm management written by Roman author Marcus Terentius Varro includes this entry:

The instruments by which the soil is cultivated. Some men divide these into three categories (1) articulate instruments, i.e. slaves. (2) inarticulate instruments, i.e., oxen. (3) mute instruments, i.e., carts. (Shelton, Jo-Ann. As the Romans Did: a Sourcebook in Roman Social History. Oxford University Press, 1998.)

A Roman woman dressed and groomed by her slaves

The Romans, however, were not ones to waste resources. Educated captives and skilled laborers worked in their masters' businesses as accountants, salesclerks, farm managers, secretary scribes, surveyors, artists, and nearly every job the empire held.

Slaves contributed to family life in trusted roles as nannies, midwives, doctors, teachers, entertainers, and household managers. A good cook was worth her weight in salt, a valuable commodity.

Household slaves, having more opportunity to form relationships with their masters, were generally treated better than slaves working at farms, mines, or factories.

Talented slaves were offered freedom as an incentive for quality work. Freed slaves entered the formalized relationship of client and patron with their former owner. A powerful or wealthy patron would offer benefits to his clients in return for service and loyalty. Diaries sometimes refer to slaves as friends in endearing terms. Cicero freed his slave, Tiro, who remained a devoted secretary and companion to Cicero until his death. A practice called manumission, freed family slaves, often when the master died. Some slaves refused offers of freedom when their loyalty was to the family, or a slave with no livelihood would end up on the street and destitute. An owner could grant independence to reward a slave's contribution to the master, business, or household. A freed slave often continued the same duties for their former master. Slaves could own property and purchase their freedom if their owner agreed.

Tomb of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces the baker. (Wikipedia CC, Livioandronico2013)

This tomb is one of many lavish tombs created by freedmen. These men were at first slaves, but, with the help of their masters, they were able to earn money to buy their freedom and begin their businesses. Apart from the occasional slave riots and uprising, which the ruling class rightly feared, the evil of slavery remained an unchallenged part of Roman society until its demise. We judge the Romans harshly, but every human culture, religion, and society, including ours, have institutionalized some form of slavery or servitude. This segues into a blog for another day: A God-given right to freedom.

More posts

January 26, 2025

0 Comments5 Minutes

Spectacles of Rome: Bathing, Blood, and Chariots (Part 1 Bathing)

July 3, 2024

0 Comments1 Minutes

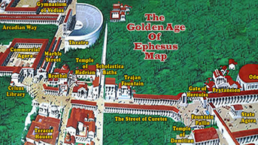

Interested in Fortunes of Death book two in the Secrets of Ephesus series?

January 11, 2022

0 Comments7 Minutes

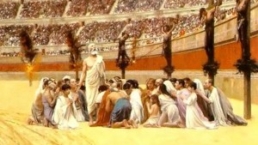

Christian Persecution

Christian persecution in 96 AD/CE, the era of "Obedient unto Death", was not an all-out war against Christians. The Romans, in general, were tolerant of diverse religions; What got Christians in…

February 8, 2021

0 Comments5 Minutes

Grilled sow’s womb for dinner, anyone?

In my upcoming book Obedient unto Death, describing meals eaten 2000 years ago can prove interesting. In a previous blog, I discussed the seating chart at a Roman dinner party—the host assigned…

January 13, 2021

0 Comments4 Minutes

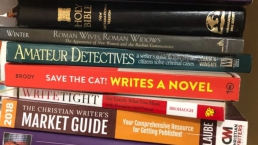

It is Really Happening?

My new year started with a huge celebration!!!! CrossRiver Media accepted my historical mystery novel Obedient unto Death for publication, with a target launch date of December of 2021. Getting…

October 9, 2020

0 Comments1 Minutes

A writing journey: inspiration

I can't pinpoint the exact moment in my life when inspiration struck, and I knew I had to drop everything and write. Many writers say they knew they wanted to be an author the first time they picked…

October 9, 2020

0 Comments5 Minutes

Treacherous Topic part 1

When we attempt to relate to another culture, especially one existing over 2500 years ago, confusion, bewilderment, and in the case of slavery, rage is bound to happen. The culture of slavery is an…

August 30, 2020

0 Comments4 Minutes

If you eat with your fingers you might be a Roman.

In my murder #mystery novel “Obedient unto Death,” I needed to describe a formal Roman dinner. I have watched movies portraying Roman dinner parties, but watching and writing about them are two…

July 25, 2020

2 Comments2 Minutes

Providence – God’s Plan for Me

I have lost count of the times I have been astounded and amazed by God’s providence. I keep saying I should record all the miracles that have transpired, the “coincidences,” the “I can’t believe it”…

July 22, 2020

0 Comments4 Minutes

A Most Appreciated Bible Verse

At this juncture of life, Psalm 46:10 is the verse I find myself turning to again and again for reassurance, advice, and focus. “Be still, and know that I am God...” (KJV) This advice was front and…

March 31, 2019

0 Comments2 Minutes

Faith musings

I am sad today. A young hummingbird flew into our house yesterday, and the situation did not end well. We have cathedral ceilings, and it flew straight up to the 16-foot-high peak and stayed there.